Python 3 input and output

Python 3 Input and Output

In the previous chapters, we’ve already touched upon the input and output capabilities of Python. This chapter will cover Python’s input and output in detail.

Output Formatting

Python has two ways to output values: using expressions and the print() function.

A third way is to use the write() method of a file object. The standard output file can be referenced by sys.stdout.

If you want a more versatile output format, you can use the str.format() function to format the output value.

If you want to convert the output value into a string, you can use the repr() or str() functions.

- str(): This function returns a human-readable representation.

- repr(): This function produces a representation that is easy for the interpreter to read.

For example

>>> s = 'Hello, Geekdoc'<br>

>>> str(s)<br>

'Hello, Geekdoc'<br>

>>> repr(s)<br>

"'Hello, Geekdoc'"<br>

>>> str(1/7)<br>

'0.14285714285714285'<br>

>>> x = 10 * 3.25<br>

>>> y = 200 * 200<br>

>>> s = 'The value of x is: ' + repr(x) + ', The value of y is: ' + repr(y) + '...'<br>

>>> print(s)<br>

The value of x is: 32.5, the value of y is: 40000...<br>

>>> # The repr() function can escape special characters in a string<br>

... hello = 'hello, Geekdocn'<br>

>>> hellos = repr(hello)<br>

>>> print(hellos)<br>

'hello, Geekdocn'<br>

>>> # The parameter of repr() can be any Python object<br>

... repr((x, y, ('Google', 'Geekdoc')))<br>

"(32.5, 40000, ('Google', 'Geekdoc'))"<br>

Here are two ways to output a table of squares and cubes:

>>> for x in range(1, 11):<br>

... print(repr(x).rjust(2), repr(x*x).rjust(3), end=' ')<br>

... # Note the use of 'end' in the previous line<br>

... print(repr(x*x*x).rjust(4))<br>

...<br>

1 1 1<br>

2 4 8<br>

3 9 27<br>

4 16 64<br>

5 25 125<br>

6 36 216<br>

7 49 343<br>

8 64 512<br>

9 81 729<br>

10 100 1000<br>

<br>

>>> for x in range(1, 11):<br>

... print('{0:2d} {1:3d} {2:4d}'.format(x, x*x, x*x*x))<br>

...<br>

1 1 1<br>

2 4 8<br>

3 9 27<br>

4 16 64<br>

5 25 125<br>

6 36 216<br>

7 49 343<br>

8 64 512<br>

9 81 729<br>

10 100 1000<br>

Note: In the first example, spaces between columns are added by print().

This example demonstrates the rjust() method of string objects, which right-justifies a string and pads it with spaces on the left.

There are similar methods like ljust() and center(). These methods don’t write anything; they simply return the new string.

Another method, zfill(), fills the left side of the number with 0, as shown below:

>>> '12'.zfill(5)<br>

'00012'<br>

>>> '-3.14'.zfill(7)<br>

'-003.14'<br>

>>> '3.14159265359'.zfill(5)<br>

'3.14159265359'<br>

The basic usage of str.format() is as follows:

>>> print('{}网址: "{}!"'.format('Geek Tutorial', 'www.geek-docs.com'))<br>

Geek Tutorial URL: "www.geek-docs.com!"<br>

The characters within the brackets (called formatting fields) are replaced by the arguments passed to format().

The numbers within the brackets refer to the position of the object passed to format(), as shown below:

>>> print('{0} and {1}'.format('Google', 'Geekdoc'))<br>

Google and Geekdoc<br>

>>> print('{1} and {0}'.format('Google', 'Geekdoc'))<br>

Geekdoc and Google<br>

If keyword arguments are used in format(), their values refer to the arguments with that name.

>>> print('{name} website: {site}'.format(name='Geek Tutorial', site='www.geek-docs.com'))<br>

Geek Tutorial website: www.geek-docs.com<br>

Positional and keyword arguments can be combined arbitrarily:

>>> print('Site list {0}, {1}, and {other}.'.format('Google', 'Geekdoc', other='Taobao'))<br>

Site list Google, Geekdoc, and Taobao. <br>

!a (using ascii()), !s (using str()), and !r (using repr()) can be used to convert a value before formatting it:

>>> import math<br>

>>> print('The approximate value of the constant PI is: {}.'.format(math.pi))<br>

The approximate value of the constant PI is: 3.141592653589793. <br>

>>> print('The approximate value of the constant PI is: {!r}.'.format(math.pi))<br>

The approximate value of the constant PI is: 3.141592653589793. <br>

An optional : and format specifier can follow the field name. This allows for more refined formatting of the value. The following example rounds Pi to three decimal places:

>>> import math<br>

>>> print('The constant PI has an approximate value of {0:.3f}.'.format(math.pi))<br>

The constant PI has an approximate value of 3.142. <br>

Passing an integer after the : ensures that the field is at least that wide. This is useful for prettifying tables.

>>> table = {'Google': 1, 'Geekdoc': 2, 'Taobao': 3}<br>

>>> for name, number in table.items():<br>

... print('{0:10} ==> {1:10d}'.format(name, number))<br>

... <br>

Google ==> 1<br>

Geekdoc ==> 2<br>

Taobao ==> 3<br>

If you have a long format string and don’t want to break it up, it’s helpful to format by variable name rather than position.

The simplest way is to pass in a dictionary and then use square brackets [] to access the key values:

>>> table = {'Google': 1, 'Geekdoc': 2, 'Taobao': 3}<br>

>>> print('Geekdoc: {0[Geekdoc]:d}; Google: {0[Google]:d}; Taobao: {0[Taobao]:d}'.format(table))<br>

Geekdoc: 2; Google: 1; Taobao: 3<br>

You can also achieve the same functionality by using ** before the table variable:

>>> table = {'Google': 1, 'Geekdoc': 2, 'Taobao': 3}<br>

>>> print('Geekdoc: {Geekdoc:d}; Google: {Google:d}; Taobao: {Taobao:d}'.format(**table))<br>

Geekdoc: 2; Google: 1; Taobao: 3<br>

Old-Style String Formatting

The % operator can also be used for string formatting. It takes the left argument as a format string similar to sprintf(), substitutes the right argument, and returns the formatted string. For example:

>>> import math<br>

>>> print('The constant PI is approximately %5.3f.' % math.pi)<br>

The constant PI is approximately 3.142. <br>

Because str.format() is a relatively new function, most Python code still uses the % operator. However, since this legacy formatting method will eventually be removed from the language, str.format() should be used more often.

Reading Keyboard Input

Python provides the input() built-in function to read a line of text from standard input, which defaults to the keyboard.

input takes a Python expression as input and returns the result of the operation.

Example

#!/usr/bin/python3<br>

<br>

str = input("Please input: ");<br>

print ("Your input is: ", str)<br>

This will produce the following output corresponding to the input:

Please input: Geek Tutorial

Your input is: Geek Tutorial

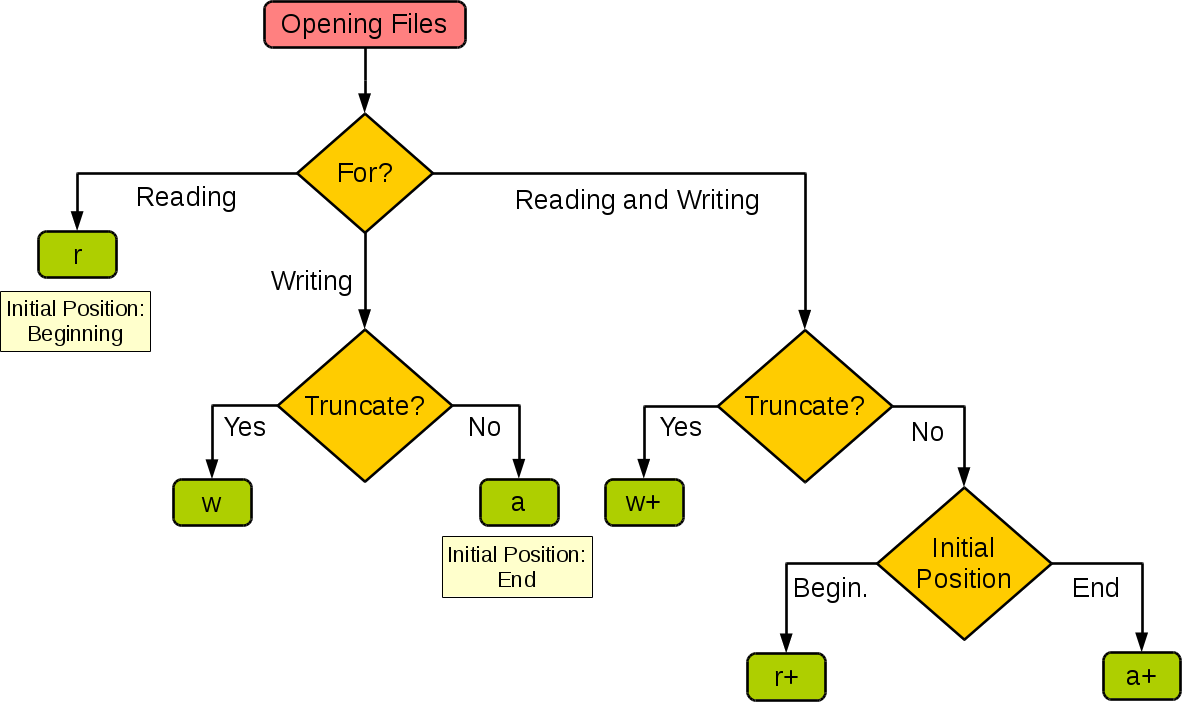

Reading and Writing Files

open() will return a file object. The basic syntax is as follows:

open(filename, mode)

- filename: A string value containing the name of the file you want to access.

- mode: Determines the mode in which the file is opened: read-only, write-only, append-only, etc. See the following for a complete list of possible values. This parameter is optional; the default file access mode is read-only (r).

Full list of different file opening modes:

| Mode | Description |

|---|---|

| r | Opens the file for read-only access. The file pointer will be placed at the beginning of the file. This is the default mode. |

| rb | Opens a file in binary format for read-only access. The file pointer will be placed at the beginning of the file. |

| r+ | Opens a file for both reading and writing. The file pointer will be placed at the beginning of the file. |

| rb+ | Opens a file in binary format for both reading and writing. The file pointer will be placed at the beginning of the file. |

| w | Opens a file for writing only. If the file already exists, it will be opened for editing starting at the beginning, with all existing content deleted. If the file does not exist, a new file will be created. |

| wb | Opens a file in binary format for both reading and writing. If the file already exists, it will be opened for editing starting at the beginning, with all existing content deleted. If the file does not exist, a new file will be created. |

| w+ | Opens a file for both reading and writing. If the file already exists, it will be opened for editing starting at the beginning, with all existing content deleted. If the file does not exist, a new file will be created. |

| wb+ | Opens a file in binary format for both reading and writing. If the file already exists, it is opened and edited from the beginning, deleting any existing content. If the file does not exist, a new file is created. |

| a | Opens a file for appending. If the file already exists, the file pointer is placed at the end of the file. That is, the new content is written after the existing content. If the file does not exist, a new file is created for writing. |

| ab | Opens a file in binary format for both reading and writing. If the file already exists, the file pointer is placed at the end of the file. That is, the new content is written after the existing content. If the file does not exist, a new file is created for writing. |

| a+ | Opens a file for both reading and writing. If the file already exists, the file pointer is placed at the end of the file. The file is opened in append mode. If the file does not exist, a new file is created for reading and writing. |

| ab+ | Opens a file in binary format for appending. If the file already exists, the file pointer is placed at the end of the file. If the file does not exist, a new file is created for reading and writing. |

The following diagram summarizes these modes well:

| Mode | r | r+ | w | w+ | a | a+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| read | + | + | + | + | ||

| Write | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Create | + | + | + | + | ||

| Overlay | + | + | ||||

| Pointer at the beginning | + | + | + | + | ||

| Pointer at end | + | + |

The following example writes a string to the file foo.txt:

Example

#!/usr/bin/python3<br>

<br>

# Open a file<br>

f = open("/tmp/foo.txt", "w")<br>

<br>

f.write("Python is a very good language. Yes, it is very good!!")<br>

<br>

# Close the open file<br>

f.close()<br>

- The first parameter is the name of the file to be opened.

- The second parameter describes the character set used by the file. mode can be ‘r’ for read-only, ‘w’ for write-only (if a file with the same name already exists, it will be deleted), and ‘a’ for appending to the file; any data written is automatically added to the end. ‘r+’ is used for both reading and writing. The mode argument is optional; ‘r’ is the default.

This opens the file foo.txt, which displays the following:

$ cat /tmp/foo.txt

Python is a very good language.

Yes, it really is!!

File Object Methods

The remaining examples in this section assume that a file object called f has been created.

f.read()

To read the contents of a file, call f.read(size), which reads a certain amount of data and returns it as a string or bytes object.

size is an optional numeric parameter. If size is omitted or negative, the entire file is read and returned.

The following example assumes that the file foo.txt already exists (created in the example above):

Example

#!/usr/bin/python3<br>

<br>

# Open a file<br>

f = open("/tmp/foo.txt", "r")<br>

<br>

str = f.read()<br>

print(str)<br>

<br>

# Close the open file<br>

f.close()<br>

Executing the above program will produce the following output:

Python is a very good language.

Yes, it's really good!!

<h3>f.readline()</h3>

<p>f.readline() reads a single line from a file. The newline character is 'n'. If f.readline() returns an empty string, it means the last line has been read.</p>

<p><strong>Example</strong></p>

<pre><code class="language-python line-numbers">#!/usr/bin/python3<br>

<br>

# Open a file<br>

f = open("/tmp/foo.txt", "r")<br>

<br>

str = f.readline()<br>

print(str)<br>

<br>

# Close the open file<br>

f.close()<br>

Executing the above program will print:

Python is a very good language. f.readlines()

f.readlines() returns all the lines contained in the file.

If the optional parameter sizehint is set, it reads the specified number of bytes and splits them into lines.

Example

#!/usr/bin/python3<br>

<br>

# Open a file<br>

f = open("/tmp/foo.txt", "r")<br>

<br>

str = f.readlines()<br>

print(str)<br>

<br>

# Close the open file<br>

f.close()<br>

Executing the above program will output:

['Python is a very good language. n', 'Yes, it's really good!!n']

Another way is to iterate over a file object and read each line:

Example

#!/usr/bin/python3<br>

<br>

# Open a file<br>

f = open("/tmp/foo.txt", "r")<br>

<br>

for line in f:<br>

print(line, end='')<br>

<br>

# Close the open file<br>

f.close()<br>

Executing the above program will print:

Python is a very good language.

Yes, it is very good!!

This method is simple, but it doesn’t provide a lot of control. Because the two methods have different processing mechanisms, it is best not to mix them.

f.write()

f.write(string) writes string to a file and returns the number of characters written.

Example

#!/usr/bin/python3<br>

<br>

# Open a file<br>

f = open("/tmp/foo.txt", "w")<br>

<br>

num = f.write("Python is a very good language. Yes, it is very good!!")<br>

print(num)<br>

# Close the open file<br>

f.close()<br>

Executing the above program will output:

29

If you want to write something that is not a string, you will need to convert it first:

Example

</pre>

<p>Execute the above program to open the foo1.txt file:

<pre><code class="language-python line-numbers">$ cat /tmp/foo1.txt

('www.geek-docs.com', 14)

f.tell()

f.tell() returns the current position of the file object, which is the number of bytes from the beginning of the file.

f.seek()

To change the current position in a file, use the f.seek(offset, from_what) function.

The value of from_what: 0 indicates the beginning, 1 indicates the current position, and 2 indicates the end of the file. For example:

- seek(x,0): Moves x characters from the starting position (i.e., the first character of the first line of the file).

- seek(x,1): Moves x characters backward from the current position.

- seek(-x,2): Moves x characters forward from the end of the file.

The default value of from_what is 0, which indicates the beginning of the file. Here is a complete example:

>>> f = open('/tmp/foo.txt', 'rb+')<br>

>>> f.write(b'0123456789abcdef')<br>

16<br>

>>> f.seek(5) # Move to the sixth byte of the file<br>

5<br>

>>> f.read(1)<br>

b'5'<br>

>>> f.seek(-3, 2) # Move to the third-to-last byte of the file<br>

13<br>

>>> f.read(1)<br>

b'd'<br>

f.close()

In text files (those opened without the b option), positioning is done relative to the beginning of the file.

When you’re done with a file, call f.close() to close the file and release system resources. Any attempt to access the file again will result in an exception.

>>> f.close()<br>

>>> f.read()<br>

Traceback (most recent call last):<br>

File "<stdin>", line 1, in ?<br>

ValueError: I/O operation on closed file<br>

When working with a file object, it’s a good idea to use the with keyword. It will help you properly close the file when you’re done. It’s also shorter to write than a try-finally block:

>>> with open('/tmp/foo.txt', 'r') as f:<br>

... read_data = f.read()<br>

>>> f.closed<br>

True<br>

File objects have other methods, such as isatty() and trucate(), but these are rarely used.

The pickle Module

Python’s pickle module implements basic data serialization and deserialization.

The pickle module’s serialization operations allow us to save object information from a program to a file for permanent storage.

The pickle module’s deserialization operations allow us to recreate objects previously saved from a file.

Basic interface:

pickle.dump(obj, file, [,protocol])

With the pickle object, you can open the file for reading:

x = pickle.load(file)

Note: Reads a string from file and reconstructs it into the original Python object.

file: A file-like object with read() and readline() interfaces.

Example 1

#!/usr/bin/python3<br>

import pickle<br>

<br>

# Use the pickle module to save the data object to a file<br>

data1 = {'a': [1, 2.0, 3, 4+6j],<br>

'b': ('string', u'Unicode string'),<br>

'c': None}<br>

<br>

selfref_list = [1, 2, 3]<br>

selfref_list.append(selfref_list)<br>

<br>

output = open('data.pkl', 'wb')<br>

<br>

# Pickle dictionary using protocol 0.<br>

pickle.dump(data1, output)<br>

<br>

# Pickle the list using the highest protocol available.<br>

pickle.dump(selfref_list, output, -1)<br>

<br>

output.close()<br>

Example 2

#!/usr/bin/python3<br>

import pprint, pickle<br>

<br>

#Use the pickle module to reconstruct python objects from files<br>

pkl_file = open('data.pkl', 'rb')<br>

<br>

data1 = pickle.load(pkl_file)<br>

pprint.pprint(data1)<br>

<br>

data2 = pickle.load(pkl_file)<br>

pprint.pprint(data2)<br>

<br>

pkl_file.close()<br>